Every occupation and/or art generates its own language for many reasons. The tradition of seafaring goes back almost as far as civilization and is said to be in the running for the title of the oldest profession. It has, as a result, developed a rich language of its own derived from many languages and cultures reaching back through time.

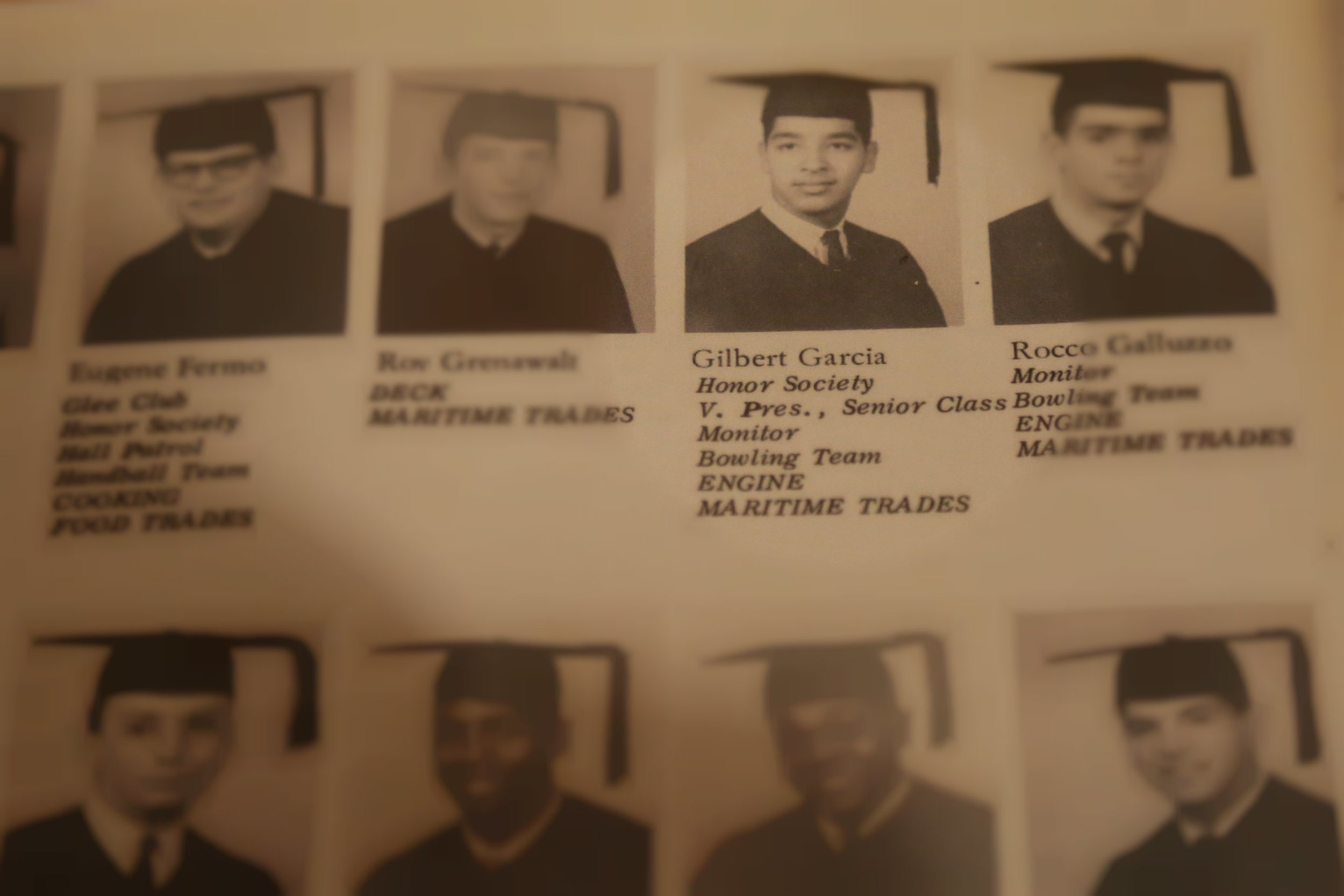

Part of the unofficial mission of Project Liberty Ship and the crew of the JOHN W. BROWN is to not only memorialize the history of Liberty Ships in general and one Liberty Ship in particular but to help preserve the language and traditions of the maritime community. Seafarers have made what is considered “modern society” possible (regardless of when in history one defines modern) through the not so simple act of moving goods across the globe at a cost which makes the products of one nation affordable anywhere on the globe. The maritime industry and the seamen who are an indispensable part of it have learned to communicate across national and cultural barriers and have created a unique culture with its own language and customs.

I have been asked why it is so important to remember that we are standing on a deck or that you can lean against a floor but you cannot stand on a floor without hurting your feet. The answer is simple. If you want to become a part of anything you must first learn the language. Maritime language is specific in its nature and is practiced not to maintain a separation from common people but in order to ensure that important information can be transmitted clearly and precisely during times of danger, high stress, adverse weather, poor hearing conditions and the lack of any common language save that of the sea. It is unthinkable that when sailing in heavy weather one could tell someone (while shouting over the wind’s roar) to “go up there and slip that rope, from the sail up there, around that round thingie so I can turn down wind”. A mariner would simply say “go forward and ease the sheet while I bear off”. Another good example would be don’t say “there is a ship or something, over there (pointing in a general way) which looks like it’s getting bigger, moving from right to left (said while facing aft and gesturing with your right and left hands)”. Far better and less likely to cause, at a minimum a number of questions, would be “there is a ship on the starboard bow moving from stbd. to port and closing”. This rather unambiguous report would tell the person in charge everything he needs to know in order to keep the vessel safe.

So I present my first attempt at “Nauti-language”. This is a glossary of maritime language based on what I have been taught during years of bumping up against the culture of the seafarer. I began this project believing that I could cross check things and take the cultural high ground. I find that it is much more difficult and resource intensive than I would have imagined. I will try to confirm the meaning of the words and phrases I include and am sure (and welcome) that some of my pronouncements will generate debate.

I hope you enjoy my glossary of Nauti-language.

Regards,

Richard Bauman

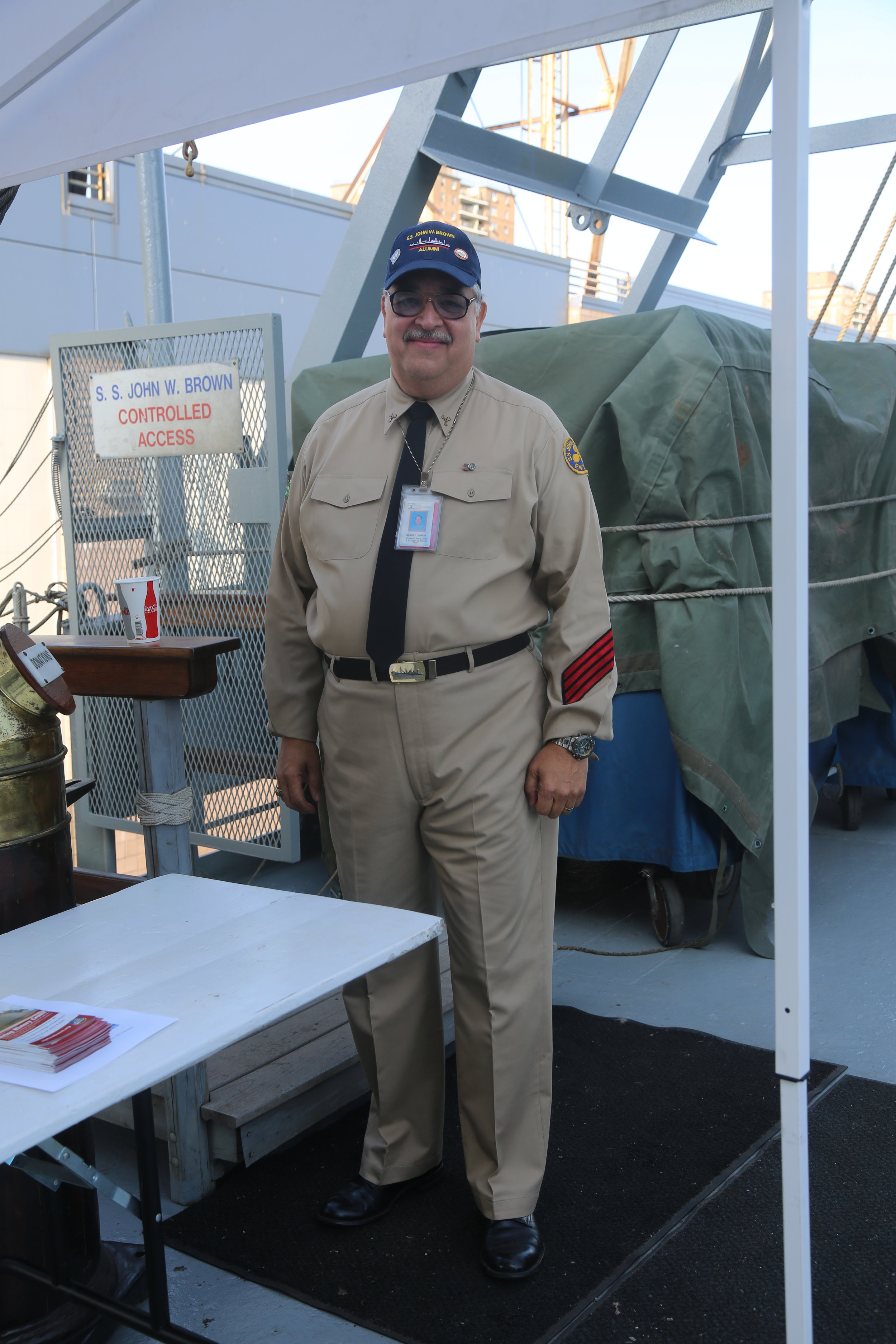

Able Seaman: The second rank for unlicensed deck persons in the deck department. Often abbreviated as A.B. Originally this rating was granted to men who could “set, reef and steer”. An A.B. is still assumed to be a person who can and will go aloft. The term “able bodied” has no history in the maritime or naval services and is a good indicator that a “lubber” is speaking. Here are pictures of crew in the deck department. Not all of them are A.B.'s but many are.

Lubber: Derisive term for an un-seaman-like person, reportedly derived from “land lover. Its not a term we usually use, since we're TRYING to get more visitors and passengers on the ship.

Aloft: Overhead especially up the mast. When a sailor dies he is said to have gone aloft.

Above: To go above is to move to a higher deck or up onto the open deck.

Alow: Everything which is below the deck. It is also a term to describe a sailing vessel when drifting down wind, due to heavy weather or abandonment.

Below: To go below is to move to a lower deck or to go into the house or hull and “out of the weather”.

Master: The captain of a merchant vessel - due to the fact that the officer in charge must obtain a master’s certificate before taking command. Derived from an old naval rank at first equal to lieutenant and later commander, the master was in charge of navigation. The title of captain was reserved for the military officer in charge of a naval vessel. Later the term “master and commander” was assigned to the senior naval officer.

Note: There is no certificate or license for captain! When someone says they have a “captain’s” license they have never bothered to read the certificate they hold. Even naval officers are captain by virtue of their military orders not a license!

Mate: In naval ratings a mate is a petty officer serving under a warrant officer, such as Boatswain’s mate. On merchant vessels a mate is next in line of command after the master. Today the mates are ranked 1st, 2nd and 3rd according to the license they hold and their experience level.

Flake: To lay out a line or chain up and down the deck so that the whole length is exposed.

Fiddle: A rack fixed to a table to stop things from sliding off.

Floor: The bottom part of the frames where they become horizontal or nearly so. The floors of modern ships are almost always in the bilge or double- bottoms and form, with the keel, the structural backbone of the vessel. The floor in a steel ship is a piece of steel plate stood on edge and athwartships, thus “you can stand on the floor but you’ll hurt your feet”.

Deck: The nautical name for what would be a floor in a building ashore. A deck inside the hull must reach from side to side but not necessarily all the way from stem to stern.

Ceiling: The planking or any material which covers the inside of any compartment on a vessel. The ceiling may cover the overhead, bulkheads or even the floors where they are not covered with a deck. A ceiling is any interior structure which prevents direct viewing of the structural components of a vessel.

Bulkhead: A vertical partition either athwartship or fore and aft.

Escutcheon: A shield or plate hung from the stern of a vessel showing its name and port of registry. Often escutcheons were very elaborate on sail vessels but modern regulation requires the same information be painted directly on the hull.

Stem: The fore most part of a vessel’s hull; the bow. The part of the hull which cuts the water when a vessel is moving forward.

Stern: The after most part of the hull. The stern may have many shapes from fine to round to a flat transom. The stern is often the most expensive part of the hull to build and to repair as its structure is intricate and must accommodate the rudder(s) and propeller(S) as well as be strong enough to withstand overtaking seas.

Starboard: The right side and direction of a vessel when looking forward. It is believed to have been derived from the term “steer board”. One of the first methods of steering a vessel was with a board or oar trailed behind the ship. Early ships generally had a high stern post and the steering board was usually lashed to the right side of this post, thus becoming known as the “steer board side”.

Port: The left side and direction of a vessel when looking forward. Originally called the larboard side this term was easily confused with starboard and was abandoned in favor of port. (The British were one of the last maritime nations to do so!) Port is generally believed to have derived from the fact that the “steer board” side of a ship was not the best side to land against a pier due to the possibility of damaging the steer board. The left side of the ship was the best side to land at a port for unloading and thus the name port side!

Stay tuned for more Nauti-language coming to a blog near you, soon. Thanks for reading and following us.

Project Liberty Ship, Inc is a 501(c)3 non-profit, all volunteer organization engaged in the preservation and operation of the historic ship JOHN W. BROWN as a living memorial museum. Gifts to Project Liberty Ship are tax deductible.